Introduction

Early childhood teacher education involves challenging students to consider questions about power relations between children and adults, and children’s agency in kindergarten. The concept of ‘resistance’ can be understood as essential in order to develop a democratic practice in kindergarten (for example, Biesta, 2012). In recent years, ‘resistance’ as a phenomenon has aroused interest in the field of kindergarten research. Øksnes and Samuelsson (2017a), for example, see actions that break with norms or rules as something other than disobedience in their anthology. Such actions may be, to a greater or lesser extent, a conscious resistance to being defined or controlled. ‘Resistance’ is also understood as a bodily reaction to being forced into a tempo and rhythm that can feel destructive. The democratic potential lies in turning opposition into an opportunity to increase justice and resistance in dialogue. But how can early childhood education students recognise, reflect on and work with notions of resistance to inform their teaching? This article explores this research question by using young children’s photographs as a springboard for students’ explorations of such ideas. The aim is to see what happens when the concepts of resistance and multiple listening (Rinaldi, 2005, 2006) are brought together with thinking about slow pedagogies (Clark, 2020, 2023).

Context

The context for this article is a case study based on an engagement with Norwegian students enrolled in a Master’s programme in pedagogy that focuses on kindergarten management. The case study was conducted during the course ‘Children as actors’ that explores the roles of children, teachers and the environment in democratic practice. This case study is part of a wider research study: ‘Children’s Photographic Expressions’ (Pettersvold & Nordtømme, 2019), referred to in this article as the ‘main study’. This was a collaborative inquiry to celebrate and promote the 30th anniversary of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. The main study involved 39 five-year-old children from four kindergartens in Horten municipality, Norway’s National Museum of Photography (Preus Museum) and ourselves as early childhood teacher educators at the University of South-Eastern Norway. The main study included a photographic exhibition (held at the Preus Museum from 18 August 2019–5 January 2020, and subsequently online)1 experimenting with children’s photographs as pedagogical documentation in kindergartens and in a museum. Since this was the children’s last year of kindergarten before starting school, the children were asked: ‘What photographs do you want to take to remember the kindergarten?’ This question became the frame for the main study.

This article focuses on the Master’s degree students’ engagement with the young children’s photographs to explore the concept of resistance.

Multiple listening

Photographs as a site of multiple listening invite an extended dialogue between children and adults. Rinaldi (2006) demonstrated how listening is more than hearing and showed that multiple listening is an ethical way of communicating with children. Multiple listening demands an openness of thought, openness to the unknown and a suspension of judgement. Both in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) and in early childhood teacher education, multiple listening is an important practice for children and students as part of active engagement in institutional life as it exists, but also as a generator of new ideas and possibilities.

Pedagogical documentation, as it originated in the municipal preschools of Reggio Emilia in northern Italy, can invite multiple listening not only in working with children, but also with students in early childhood teacher education. To use drawings or photographs as a tool for multiple listening creates opportunities for discussion and debate around the visual and verbal material gathered in learning encounters (Formosinho & Peeters, 2019; Rinaldi, 2006; Vecchi, 2010). Peter Moss identifies how this can be part of a democratic process:

Pedagogical documentation can be described as a process of making processes (such as learning) and practices (such as project work) visible and therefore subject to reflection, dialogue, interpretation and critique. It involves, therefore, both documentation itself through the production and selection of varied material (eg. photographs, videos, tape recordings, notes, children’s work etc) and discussion and analysis of this documentation in a rigorous, critical and democratic way.

(Moss, 2019, p. 85)

The way is opened for different voices and wider perspectives by drawing on a range of modes of communication with children. But as Moss (2019) underlines, discussion is a vital part of engaging with these different modes or materials. Traditional or normative listening only hears what is expected whereas Moss is advocating for a form of listening to all channels that is open to the unexpected. Analysing children’s photographs (whether within day-to-day practice in kindergarten or in the context of a research study) could fall into a normative form of listening, without the determination to be open to alternative narratives. Photographs as pedagogical documentation or empirical material will always be preliminary, incomplete and possible to retell and remember again (Jackson & Mazzei, 2012, in Clark, 2019). Revisiting empirical material creates a distance from the already analysed and can challenge the already known. Lenz Taguchi (2010, p. 272) refers to this way of revisiting as a form of ‘ethics of resistance’ which can be understood as an obligation to be open to new thoughts and to challenge previously taken-for-granted perceptions and assumptions.

Slow pedagogies

Constraints imposed by the clock are a common feature of early childhood education (Pacini-Ketchabaw, 2012). However, the relationship with time is more often implicit rather than explicit and more attention is given to the impact of the spatial than the temporal on young children’s lives (Wien & Kirby-Smith, 1998). How time is approached in ECEC can have an impact on relationships with young children, parents and colleagues (Clark, 2020) and is deeply embedded in everyday culture in certain settings: for example, how are mealtimes arranged? Is there room for the unplanned as well as the planned? What value is placed on listening?

The external pressures on teachers to be seen to perform an ever-increasing number of tasks has led to what Stephen Ball (2016) describes as ‘regimes of performativity’ in his critique of neoliberal education. These pressures from increasing regulation, focusing on efficiency and testing, have also been critiqued in higher education and have an impact on both academics and students. Berg and Seeber (2016) are among those calling for a change in the teaching and learning culture in universities by embracing a slow pedagogy that enables more of a participatory rather than a transmissive form of study. The Slow Movement that began with the concept of ‘slow food’ (Honoré, 2004) has been influential in developing these ideas. Payne and Wattchaw (2009) have made the case for slow pedagogy of place in their teaching with environmental education students, in contrast to what they describe as ‘take-away pedagogies’: the ‘fast, take-away, virtual, globalised, downloadable uptake version of electronic pedagogy’ (Payne, 2006, in Payne & Wattchaw, 2009, p. 17). Key features of such an approach include an emphasis on first-hand experience, revisiting ideas and places, and creating time for exploring different perspectives. This can be understood as a form of multiple listening.

Resistance

The concept of resistance can be understood in numerous ways, as for example, in the work of Foucault (1997), Giroux (2001) or Tobin (2005). We have chosen to work with the ideas of Biesta (2012, 2013) as he makes explicit the connections between the concept of resistance, the call for a slow education and democracy. Biesta explores the way in which we can engage with the resistance we encounter when we act and take initiative. This engagement, through dialogue, is an important part of democratic practice and is central to how the relationship between the child and the world is viewed. This is about the old theme: the education of the will (Biesta, 2012, p. 92). Resistance as a phenomenon is a question of focusing attention on the connection between the child and the world rather than seeing education as focusing just on the child or the world. Biesta asks how the child can come into the world instead of putting as much world as possible into the child. The educational challenge, viewed in this way, is the double task of engagement with and emancipation from the world (Biesta, 2012, p. 94). What Biesta calls the educational space is a dialogical space between the child and the world, and includes engaging with what is resisted. Resistance understood in this way is positive and important. Education without resistance, Biesta argues, is nothing more than the monologue of the teacher. These important dialogues are open towards the world and make the pedagogy slow. This requires time and attention, endurance and perseverance (Biesta, 2012, p. 100). The underlying premise of the discussion Biesta raises is that there is a need to slow education down rather than to speed it up towards ever greater ‘perfection’, since there are no quick fixes in achieving a dialogical relationship between the self and the world (Biesta, 2012, p. 100).

A final point worth stressing here is Biesta’s emphasis on teachers meeting children’s resistance with resistance, in order to make sure that what they express is more than a spontaneous desire (Øksnes & Samuelsson, 2017b, p. 177). This aspect of the connection between resistance and democracy is featured in the discussion with the students.

The case study

Building on the ‘Children’s Photographic Expressions’ study, the case study of early childhood education students took place in February 2021, inspired by multiple listening (Rinaldi, 2005, 2006) as a method to explore the research question: how can early childhood education students recognise, reflect on and work with notions of resistance? There were two reasons for adding to the main study in this way.

Firstly, we were interested in the students’ interpretations of the photographs and how these might differ from our own as teacher educators. This acted as a form of multiple listening that is part of the analytical process. Secondly, we wanted to explore if the children’s photographs could be a springboard for a focused discussion with the students about the complex concept of resistance as part of developing a democratic practice in kindergarten. We presented the main study and discussed questions about children’s resistance and photography as a means of expression. This involved a discussion about how children may find it easier to express themselves more freely with a camera than in conversation about how they would like to remember kindergarten. But this does not mean that children’s photography is without external influences. Children may be influenced by visual conventions and regulations of various kinds. However, photographs can, in a unique way, open up dialogue about children’s perspectives.

The status of children’s photographs also depends on how one understands the photograph. In the main study, we understood photographs as capturing something as it is perceived in the present, but which in the next moment may be given a new meaning by both the photographer and the viewer. Photographs are ‘true’ in the sense that they are subjectively interpreted. As Kim Rasmussen (2013) describes, photographs are to be regarded as a visual construction. They are a transformation of reality as we experience it through the senses. They are ‘framed’, ‘timed’, ‘angled’ and have in a way become independent from reality (Rasmussen, 2013, p. 277). In other words, photographs are similar to reality, but they are not identical to it.

Following this discussion, we asked the students to make their own ‘mind map’ of different forms of children’s resistance. Then, in six groups, the students selected three of the children’s photographs in each group from the online exhibition, where they could perceive, or sense in some way, resistance. All of the students gave their consent to participate in the study.

Children’s images as a catalyst for debating the concept of resistance with students

The students identified several different ways of thinking about resistance in the children’s photographs. Three different themes emerged in the analysis that took part in two stages: firstly, with the students examining the images and the children’s texts; and secondly, as a research team, reviewing the images, the children’s texts, and the students’ comments. This is an analytical process that involves layered or multiple listening. We will illustrate the themes by presenting eight of the photographs chosen by the students.1 The three themes are: resistance to the use of space; resistance to adults’ tasks; and resistance to the timetable and curriculum. Under each theme we will begin by presenting our reflections on the individual images and the children’s captions, followed by a description of the students’ reflections in relation to the concept of resistance.

Resistance to the use of space

Yu Xiang commented about this image as follows: ‘And then there’s a prison there. Look here! This is the prison. I must have that picture.’ The photo features a mound of grass and wildflowers, with buildings in the distance. In the centre of the image is a low brick structure with a barred gate in the entrance. The child’s imagination has changed this ambiguous space into a place with a story, perhaps a scary story. It might not be what adults expect young children to want to remember about their time in kindergarten. The structure is not a piece of play equipment specifically designed for children or made by them. This is ‘real’, and could possibly make a prison game more scary and, at the same time, more amusing.

The students understood this image to point to the children’s longing for places outside the kindergarten area, for the excitement and risk of a ‘real’ playground for prison-play. The image was interpreted as resistance to purpose-built play spaces: ‘it’s like a “real” prison.’

This image is dominated by a high fence with a solid gate and cars outside. Inside the fence is a wooden table and bench. The foreground is an empty concrete surface. It is a peripheral space, not designed for play.

The resistance, according to the students who chose this image, lies in the contrast between the immediate interpretation of the photograph as a rather poor area, not designed for play, and the rich story of Yasir’s experiences of that space. Sitting at the table, playing ‘Monster hide and seek’, sweeping the ground free of sand, and using the corner as an observation post made this space a special place that Yasir wanted to remember.

Resistance to adults’ tasks

This is a close-up, rear-view image of a child in a blue rainsuit. The child’s bottom fills almost all of the frame. Daniel described the image as ‘bum’. To the students, this photo represented resistance to specific instructions, a kind of demonstration of agency to subvert adult intentions.

The fact that Daniel insisted on choosing this image for the exhibition was interpreted by some of the students as a way of disrupting the ‘official narrative’ about memories of kindergarten.

Marte described the process of taking this photo: ‘There she took a picture of me and I took a picture of her at the same time’. Framed in the centre of this outdoor image is a close-up of a girl whose camera is pointing at Marte.

The students chose this image as a benign or mild demonstration of resistance, since they interpreted it as a sign of not following the task. It might be seen as an unexpected and creative interpretation, as the question focused on ‘what do you want to remember about kindergarten?’ For the students, this photo represents an oppositional solution, by providing another way of expressing that having fun with her friend was something important to remember.

Resistance to the timetable and curriculum

This photograph shows a close-up of a high shelf. There are two large plastic boxes and squeezed between them is a smaller, tightly formed house built of lego. August described his photo as ‘Lego’. He has made and photographed this personal artefact. The students interpreted August’s image as a demonstration of the value of the squeezed-in house he had built. Perhaps there hadn’t been time to carry on with building and playing with the model within the constraints of the timetable? He no longer had access to this artefact but the camera became a tool to reinstate the importance of this object in contrast to the resources currently available to him through the timetable and curriculum.

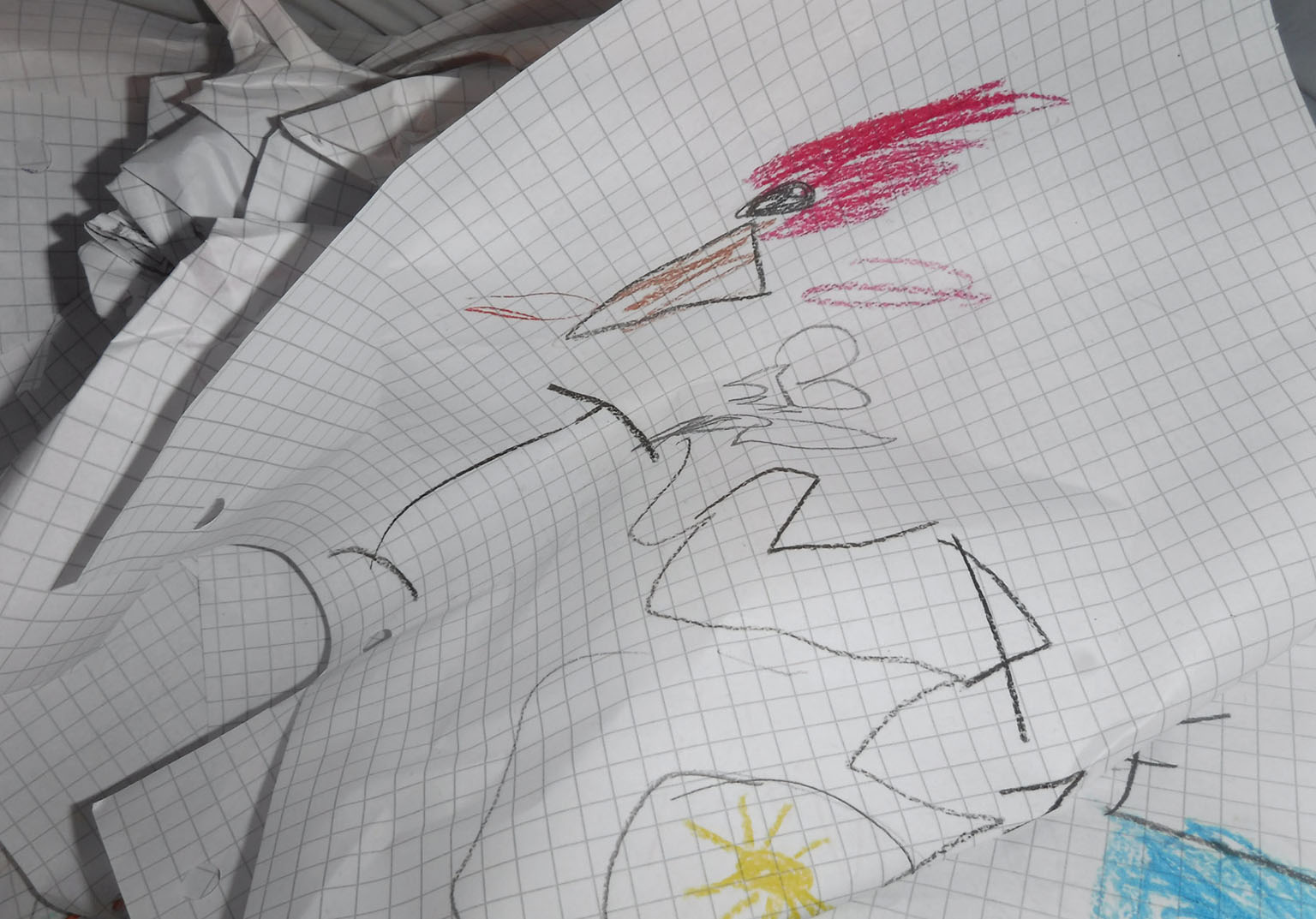

This photograph features a close-up of a crumpled drawing in a wastepaper basket. Vega explained: ‘This picture is of the bin. Someone threw out my drawing. Luckily I took a picture of it because then I can remember it forever.’

This photograph was chosen by the students as a possible demonstration of Vega’s agency in claiming back what is of personal value to her, in a similar way to August and the Lego house. The discovery of Vega’s drawing in the bin implies that the drawing was no longer of value to the teachers and is therefore treated as rubbish to be thrown away. There is a temporal dimension to the discussion about this image. Vega is clear that the value she places on this artefact is different from the adults. The students commented that she is demonstrating resistance in the form of pulling in a different direction. She also declares that the importance of this drawing is now preserved ‘forever’ by the taking and owning of the photograph.

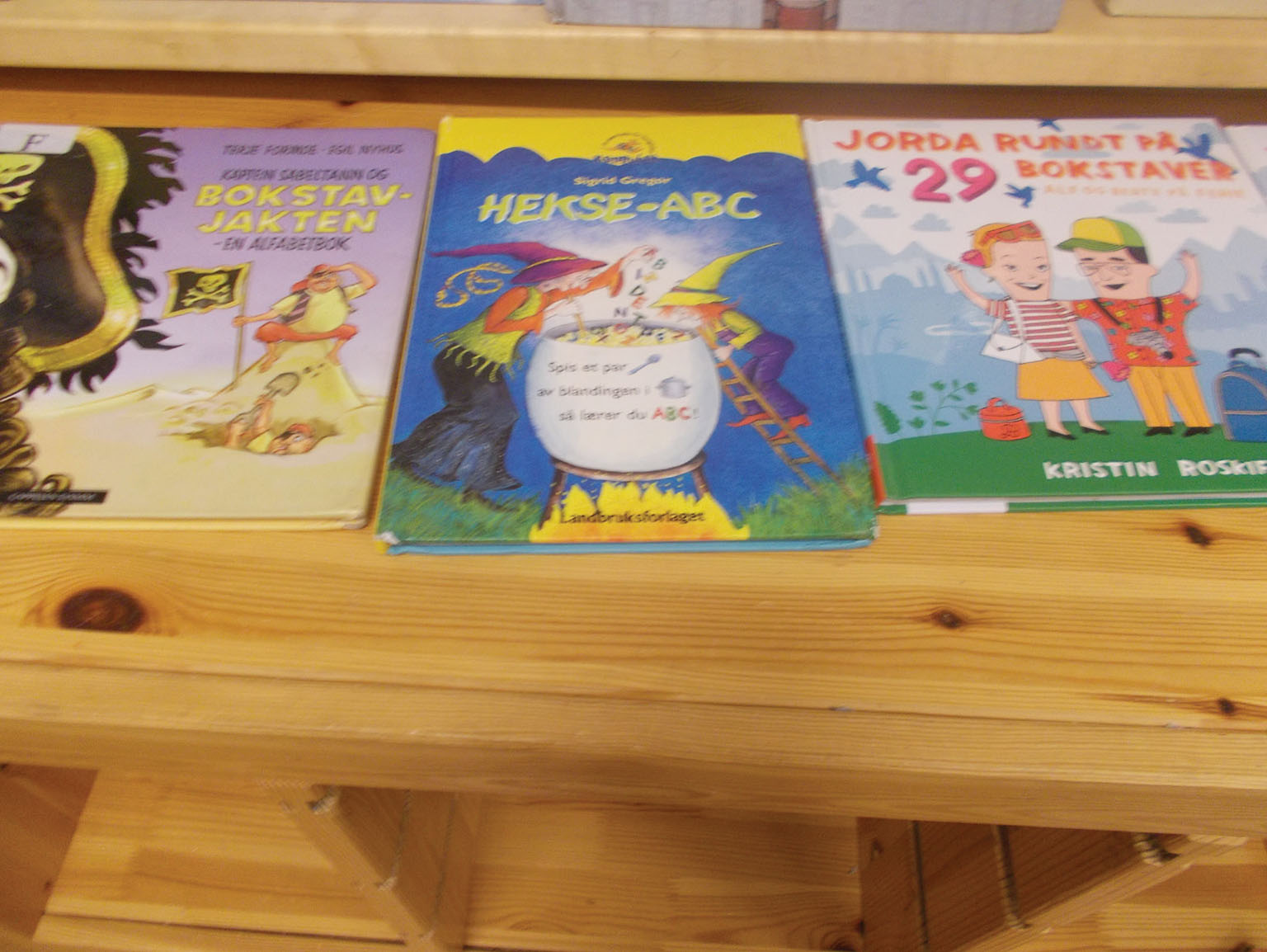

The image is a close-up view of a set of wooden shelves showing the covers of three picture books. Lidia commented: ‘Writing is great. We look in the books and write. Sometimes it gets boring. If we write for long. Not long is not boring!’

This was interpreted by the students who chose this photo as Lidia’s way to express her opinion about the way the kindergarten prepares the children to start school. With this photo, Lidia is understood by the students to be communicating that it is fun to learn to write, but maybe some flexibility regarding the time frame is lacking. The students perceived this photograph as a form of resistance to a rigid time schedule.

The final image in this theme features a tall, glass-fronted cupboard in the corner of a room with a table and chair nearby. Noah comments: ‘In there are the puzzles. It’s fun when we get to puzzle’ (meaning to be able to play with the puzzles). This image was understood by the students to demonstrate resistance to the resources available. Working with the camera as a tool, Noah was able to draw attention to what has been made inaccessible by the adults. The puzzles are hidden away and not openly available to the children. The act of taking the photograph has brought this into view.

Discussion

Images and resistance

The case study demonstrated how young children’s photographs have the potential to be a springboard for discussing complex concepts in early childhood teacher education. Working with children’s photographs gave the students opportunities, for example, to understand how children can express their views on places of significance, as demonstrated by the image of the ‘prison’ and the fence. The children’s views on adults’ tasks were in contrast to what might be expected, as shown in Daniel’s image of someone’s bottom. Sometimes children’s photographs disrupted students’ ideas of how children would remember kindergarten, for example, Marte’s photograph of her friend. Together with the students we found it interesting how they (Daniel and Marte) expressed resistance in a humorous way. The children’s responses are gentle and powerful at the same time. Students commented on how the camera could be a tool for the children to create images that have affect (Kind, 2013). This emotional impact could be felt, for example, in the photographs of the squeezed-in Lego model on the shelf and of the drawing in the bin. Similarly, this impact was noted in the images of the books, combined with Lidia’s text about writing for long as being boring, and the puzzles in the cupboard that were inaccessible to the children.

In the case study, we asked the students, as mentioned, to select images where they in some way perceived or sensed resistance that related to developing a democratic practice in kindergarten. We suggest in this article that interpreting the photographs and the texts through the identified focus of resistance has opened up for the possibility of seeing something more, as opposed to seeing ‘openly’ with no teacher-prepared agenda. We place ‘openly’ in inverted commas, as such a neutral stance is not possible: we do not see everything, and we do not see neutrally. This discussion raises awareness about the premises of the interpretations, for example, to give an identified focus – which one – or not? In this case, the focus (resistance) opened for reflections with the students about the value of resistance as positive and important, not just troublesome, and how to make it real. However, there are risks in this approach. As mentioned, not all resistance has democratic value, but it may have when it challenges privileges and positions that are taken for granted, or allows for more voices and perspectives to be heard and responded to. Students make assumptions about what they perceive, which could lead to misunderstandings about children’s priorities. Bearing this is in mind, we see the ambiguity of photography (Franklin, 2018) as a strength that can lead to alternative ways of seeing and narrating (Horsley, 2021).

This last point raises more general questions about how to talk to children about their photographs. We think that ‘emergent listening’ (Davies, 2014) is of importance here. Listening in this way is understood as listening to what we do not immediately understand or think of as relevant and what has not yet been thought of or formulated. It means listening reflectively to the prejudices that are inevitably involved when we try to understand what we hear. In the case study, it was not possible for this to happen in person as the students did not work directly with the children. This might have added an important layer to the multiple listening. But the students ‘listened’ to the photographs and the texts in what might be seen as an ‘emergent’ way, with time to reflect and discuss beyond the first glance.

Images and slowing down

The opportunity for the students to reflect together on the children’s images created a pause, maybe in the same way that Cook and Hess (2007) mean when they describe the value of this change in tempo in their own studies involving visual methods with children: ‘This repeated engagement with the children slowed down the adult journey to deciding on meanings. It gave time to think about what a child is saying, to listen again or differently, and offered the potential for new interpretations’ (p. 42). The students’ encounters did not involve the opportunity to revisit the images with the children themselves. However, the images and captions did provide a catalyst for challenging some preconceived ideas and possible meanings. The listening to each other that took place in this case study is in itself a slow process, when the time is taken to hear different perspectives and to enable different voices to be heard. This is a form of participatory pedagogy that is open to the unexpected and to uncertainty rather than a transmissive pedagogy of fixed teacher-dominated content (for example, Formosinho-Oliveira & de Sousa, 2019). We suggest that such encounters, supported by the images as a form of pedagogical documentation, can also be understood as a form of slow pedagogy, that privileges time for revisiting as well as multiple perspectives. Extending Biesta’s notion of a slow school as a place of resistance, we propose here that a ‘slow kindergarten’ might be understood as characterised by a democratic culture with time for listening to each other and for revisiting ideas, views and experiences, and where resistance is valued. As Biesta (2012) underlines, and also in our interpretation, these important dialogues are open towards the world and make the pedagogy slow. As we have described earlier in the article with reference to Biesta (2012, p. 100), this requires time and attention, and endurance and perseverance. Biesta (2012) talks about a slow school in this way:

A slow school, so I wish to suggest, is a school that takes the educational significance of the experience of resistance seriously in that it understands that it is through engagement with the experience of resistance that our worldly existence in the world and thus the existence of the world itself become possible.

(p. 101)

This reasoning emphasises the connection between resistance and, in the context of this article, a ‘slow kindergarten’ (Clark, in press). The educational space is not just a dialogical space in a harmonic way; it includes resistance. The value of resistance, besides listening to all voices, includes the possibility to look at alternatives. These might include finding other ways to organise the day, include children’s voices in planning and, as some of the images make clear, looking for more non-fragmented time for children to be immersed in play (Cuffaro, 1995).

Images and multiple listening

The students’ selection and interpretation of images from the online exhibition, together with their attention to the children’s narratives, added further layers to their reflections about resistance. The interpretations raised questions about children’s feelings about places, play, materials, time and friends. The photographs provoked discussion about feelings expressed as humour, resignation, boredom, excitement and friendship. In a similar way, Magnusson’s (2018) study raised the issue of what happens when three-year-old children are given cameras in kindergarten. She found that the children visualise narratives about everyday life that otherwise might be difficult to consider (p. 38).

To extend multiple listening, the concept of ‘resistance’ can be a lens and a way of stressing the unknown in the interpretations. Maybe the concept turned possible institutional habitual thinking upside-down and provoked the students to look for what could be a visual utterance of resistance? This perspective sharpened their view and demonstrated the extent to which children’s daily experiences seldom become visible or are articulated in the dialogue between children and teachers.

The value of looking from an unknown perspective could add another layer to multiple listening. Davies writes about the documentation practice in Reggio Emilia and of Alnervik’s practice in a Swedish kindergarten (2014, p. 25), where photographs and paintings were hung on the wall so that passers-by could contemplate them. This raises a question of proximity and distance in working with documentation. The view of the teachers close to the children and their kindergarten context is valuable in many ways. Their knowledge is both sensible and embodied as they are involved, responsible and obliged to answer to the children’s expressions. On the other hand, a more distant view could bring some new perspectives and challenge cultural or normative interpretations. To invite students to comment on or participate in analyses brings more distant perspectives into the interpretations and, at the same time, an intersubjective validation of the process involved.

Conclusion

Early childhood teacher education can offer the opportunity for students to challenge their assumptions about their future roles as teachers and also about young children’s views and perspectives. We have explored in this article the possibility of using young children’s images about kindergarten to increase students’ understanding of children’s resistance. The process we have described brings together the concept of slow and multiple listening. Drawing on Biesta (2012, 2013) we propose a starting point for thinking about what a ‘slow kindergarten’ might look like. Questions arising from this small case study suggest that students’ future teaching may be enriched by carving out time to notice and engage with young children’s resistance to the use of space, tasks and the timetable and curriculum. The next step to this research would be to enable students to work directly with young children, teachers and photography to add further depth to these enquiries and to seek practical solutions together.

References

- Ball, S. (2016). Neoliberal education? Confronting the slouching beast. Policy Futures in Education, 14(8), 1046–1059.

- Berg, M., & Seeber, B. (2016). The slow professor: Challenging the culture of speed in the academy. University of Toronto Press.

- Biesta, G. (2012). The educational significance of the experience of resistance: Schooling and the dialogue between child and world. Other Education: The Journal of Educational Alternatives, 1(1), 92–103.

- Biesta, G. (2013). The beautiful risk of education. Paradigm Publishing.

- Clark, A. (2019). ‘Quilting’ with the mosaic approach: Smooth and striated spaces in early childhood research. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 8(2), 236–251.

- Clark, A. (2020). Towards a listening ECEC system. In C. Cameron & P. Moss (Eds.), Transforming early childhood in England: Towards a democratic education (pp. 134–150). UCL Press.

- Clark, A. (2023). Slow knowledge and the unhurried child: Time for slow pedagogies in early childhood education. Routledge.

- Cook, T., & Hess, E. (2007). What the camera sees and from whose perspective: Fun methodologies for engaging children and enlightening adults. Childhood, 14(1), 29–45.

- Cuffaro, H. (1995). Experimenting with the world: John Dewey and the early childhood classroom. Teachers College Press.

- Davies, B. (2014). Listening to children: Being and becoming. Routledge.

- Formosinho, J., & Peeters, J. (Eds.). (2019). Understanding pedagogic documentation in early childhood education: Revealing and reflecting on high quality learning and teaching. Routledge.

- Formosinho-Oliveira, J., & de Sousa, J. (2019). Developing pedagogic documentation: Children and educators learning the narrative mode. In J. Formosinho & J. Peeters (Eds.), Understanding pedagogic documentation in early childhood education: Revealing and reflecting on high quality learning and teaching (pp. 32–51). Routledge.

- Foucault, M. (1997). What is critique? In L. Hochroth & S. Lotringer (Eds.), The politics of truth (pp. 23–82). Semiotext(e).

- Franklin, S. (2018). On ambiguity. https://www.magnumphotos.com/theory-and-practice/stuart-franklin-ambiguity/ Accessed 1 March 2022.

- Giroux, H. (2001). Theory and resistance in education. Towards a pedagogy for the opposition. Bergin and Garvey.

- Jackson, A., & Mazzei, L. (2012). Thinking with theory in qualitative research: Viewing data across multiple perspectives. Taylor and Francis.

- Honoré, C. (2004). In praise of slow: How a worldwide movement is challenging the cult of speed. Vintage Canada.

- Horsley, K. (2021). Slowing down: Documentary photography in early childhood. International Journal of Early Years Education, 29(4), 438–454, https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2020.1850430

- Kind, S. (2013). Lively entanglements: The doings, movements and enactments of photography. Global Studies of Childhood, 3(4), 427–441.

- Lenz Taguchi, H. (2010). Going beyond the theory/practice divide in early childhood education: Introducing an intra-active pedagogy. Routledge.

- Magnusson, L. O. (2018). Photographic agency and agency of photographs: Three-year-olds and digital cameras. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 43(3), 34–42.

- Moss, P. (2019). Alternative narratives in early childhood: An introduction for students and practitioners. Routledge.

- Pacini-Ketchabaw, V. (2012). Acting with the clock: Clocking practices in early childhood. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 13(2), 154–160.

- Payne, P. (2006). The technics of environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 12(3–4), 487–502.

- Payne, P. G., & Wattchaw, B. (2009). Phenomenological deconstruction, slow pedagogy and the corporeal turn in wild environmental/outdoor education. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 14(1), 15–32.

- Pettersvold, M., & Nordtømme, S. (2019). På kryss og tvers i barnas fotografier [Criss-cross in children’s photographs]. Barnehagefolk, 3, 27–50.

- Rasmussen, K. (2013). Forskerens fotografiske feltnoter – et bidrag til ‘thick description’? [The researcher’s photographic field notes – a contribution to ‘thick description’?]. In K. Rasmussen (Ed.), Visuelle tilgange og metoder i tværfaglige pædagogiske studier [Visual approaches and methods in interdisciplinary pedagogical studies] (pp. 261–282). Roskilde Universitetsforlag.

- Rinaldi, C. (2005). Documentation and assessment: What is the relationship? In A. Clark, A. T. Kjørholt, & P. Moss (Eds.), Beyond listening: Children’s perspectives on early childhood services (pp. 29–50). Policy Press.

- Rinaldi, C. (2006). In dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, researching and learning. Routledge.

- Tobin, J. (2005). Everyday tactics and the carnivalesque: New lenses for viewing resistance in preschool. In J. Silin (Ed.), Rethinking resistance in schools. Power, politics and illicit pleasures (pp. 32–38). Bank Street College of Education.

- Vecchi, V. (2010). Art and creativity in Reggio Emilia: Exploring the role and potentiality of ateliers in early childhood education. Routledge.

- Wien, C. A., & Kirby-Smith, S. (1998). Untiming the curriculum: A case study of removing clocks from the program. Young Children, 53(5), 8–13.

- Øksnes, M., & Samuelsson, M. (2017a). ‘Nei, jeg gjør det på min måte!’ Motstand i barnehagen. [‘No, I do it my way!’ Resistance in kindergarten.]. In M. Øksnes & M. Samuelsson (Eds.), Motstand [Resistance] (pp. 11–41). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Øksnes, M., & Samuelsson, M. (2017b). The encounter with resistance is an existential matter. Interview with Gert Biesta. In M. Øksnes & M. Samuelsson (Eds.), Motstand [Resistance] (pp. 164–181). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Notes

- 1. The photographs in this article are copyright-protected works, and they are not covered by the article's publication licence, i.e., no reuse is permitted without the express prior permission of the copyright holders. The authors have been responsible for securing permission to use all photographs herein.

Footnotes

- 1 https://www.preusmuseum.no/eng/Discover-the-Exhibitions/Previous-exhibitions/Remembrance-of-Swings-Past