Introduction

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, a young girl, Ida Thiele (1830–62), wrote several letters to her father, mostly concerning her daily life and her relationships within her family. For over a century, these letters were a well-kept secret in the Royal Danish Library, but today they testify to how a young girl negotiated the affordances and constraints of the letter as a medium in her specific historical, social and geographical setting.

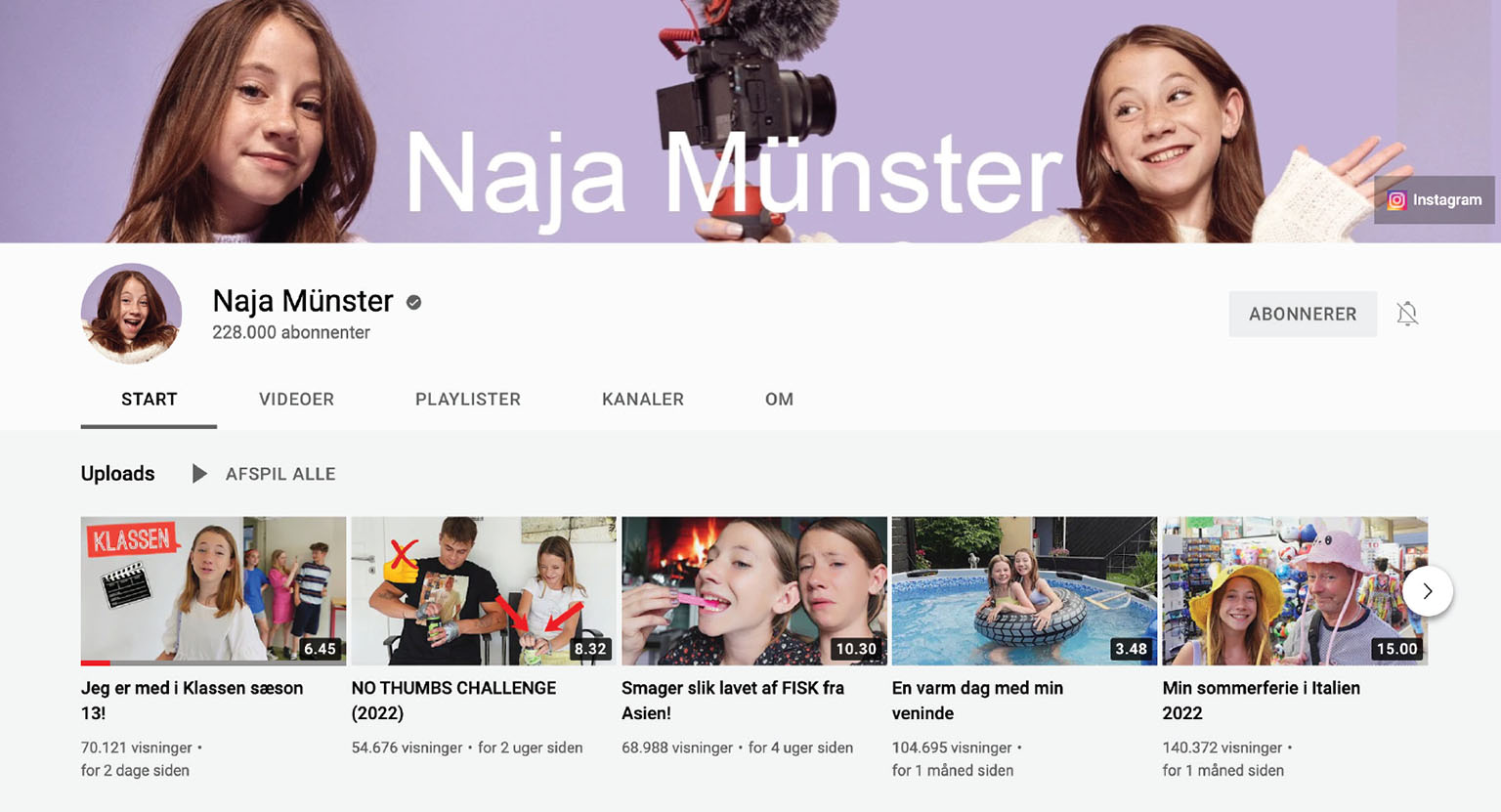

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, Naja Münster (b. 2009) was born into a family of YouTubers in a small provincial town in Denmark. In 2015, when she was six years old, Naja Münster’s YouTube channel was launched; in 2019, it reached the magic number of 200,000 followers, mainly children.

In her study of social media, Lee Humphreys states that:

When we look across media over time, we see patterns of how people are incorporating media into their everyday lives. By focusing on what people do with media, rather than on the technology, we can see similarities otherwise obscured by the newness of the platforms.

(Humphreys, 2018, p. 7).

This article reflects a similar interest in studying children’s media use throughout history. Both Naja Münster and Ida Thiele are first-person narrators who show and tell their readers or viewers about their interests and everyday lives, using the media available to them at the specific time in which they live or lived. Although these two girls’ socio-economic, technological and historical settings differ significantly, in this article we discuss possible continuities and similarities, both in relation to children as producers of media and to the content they transmit through their chosen media. Furthermore, this article examines whether and how concepts and analytical questions may meaningfully traverse history and disciplines to understand children as producers of text and media. Thus, in this article, we take the two girls’ media products as the point of departure for a transhistorical, comparative case study with an overarching research question: how can children’s media research integrate children’s perspectives on the media they use, their reasons for using specific media, and their possible agency with respect to media use?

For decades, childhood studies have encouraged paying attention to children’s voices and their agency in all contexts that include the child (James and James, 2011; James, 2007). Recently, the focus on children’s agency has developed to ‘the point of a fetish’, according to Spyrou, Rosen and Cook’s introduction to their book with the significant title, Reimagining childhood studies (2018, p. 3). In the introduction, they call for a change in focus from the individual, agentic child at the centre of research to the notion of agency as a ‘relational dynamic’ (p. 5). The focus on relational agency also draws attention to the contexts of children’s actions, as they are not ‘free from social, cultural, economic, and all other kinds of constraints’ (p. 8).

Although we find Spyrou, Rosen and Cook’s call for a focus on relational agency important, our hypothesis is that qualitative close readings of individual children as producers of texts and media provide us with knowledge that is difficult to obtain elsewhere. Paying attention to these two girls as ‘doers’ (Sparrman, 2019) and to what they choose to do with the media available to them is one way of listening to children, and it could be combined with paying attention to the ways in which they are embedded in their relationships and settings, including those communicative settings that specific media tools and platforms provide. Spyros Spyrou discusses various methodological approaches that may be used when one wishes to access ‘aspects of voice which are often left out from analysis’, and he identifies ‘silence as one such feature of voice’ (Spyrou, 2018, p. 86). He discusses aspects of ethnographic research with children, including interviews, visual methods, participant observation and peer culture research, and – like Mazzei (2009) – also suggests that researchers pay attention to ‘the undomesticated voice, the non-normative voice, “the voice in the crack”’ (Spyrou, 2018, p. 95–96). In such discussions of ways to improve research designed to listen to children’s voices, we look in vain for attention paid to the media available to children, the affordances of such media and the choices children make regarding these media when they choose to express themselves. We apply theories and concepts from media studies to argue that a focus on children as ‘doers’ is another possible pathway when we wish to hear about aspects of children’s experiences, choices and reflections or, in this case, when they learn to communicate and present themselves through selected media.

Given the foregoing background, this article first introduces the two cases on which our analysis is based. Next, we present the theoretical and methodological foundation of this article, and focus on the constraints and possibilities of combining two hitherto separate research fields and two rather different cases. Subsequently, we focus on the three overarching questions related to the two cases: how content is presented or silenced by the two children, how their selected media enable and afford their communicative practices, and finally, the degree to which they accept or challenge conventions and constraints of the said media as tools for self-presentation. In the discussion, we focus on the limitations and advantages of interdisciplinary studies of this sort and discuss the degree to which they enable us to understand the actions, utterances and silencing of children as media users and producers.

Girls’ Voices Across the Centuries: Ida Thiele and Naja Münster

Ida Thiele was born in Copenhagen, where her father, Just Mathias Thiele (1795–1874), was a professor at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Just Mathias Thiele came from a family of book printers and became part of the cultural and financial elite through his education and initiative, and through his marriage to Sophie Holten, the daughter of one of Denmark’s wealthiest men. For the first five years of her life, Ida Thiele grew up in a happy and loving home, but in 1835, her mother suddenly died of a fever. She and her sister were sent to live with their grandparents who lived in the country for most of the year, far from their father who continued to live in Copenhagen. This physical distance and the close relationship between father and daughter were the reasons for beginning the correspondence. The fact that the letters of both Ida Thiele and her father were preserved testifies to the importance of the letters as a medium for the writers.1 That a child’s letters were preserved – and that it was possible for a researcher to find them – is also remarkable, as child-authored sources are extremely rare in archives (Appel and Christensen, 2017; Sánchez-Eppler, 2013). One of the reasons Ida was able to write to her father was because she had a teacher who taught her how to write, and she also had access to paper, pen, ink and postage, privileges available to few children at that time.

One hundred and seventy-nine years after Ida Thiele’s birth, Naja Münster was born into a family of five: her mother Hanne, her father Finn and her three brothers, Dennis, Morten and Max. The family lives in Vojens, a small town in Southern Jutland, Denmark, and until Morten Münster was thirteen, they were totally unknown to the general public. At this time, however, while most of his school friends were becoming increasingly interested in computer games, Morten Münster picked up his smartphone and began filming his family and friends. Later, he taught himself to edit videos, and uploaded them to the video-sharing platform, YouTube. At this point, around 2012, YouTube was mainly a repository for all kinds of amateur content, and it was less structured than it is today in terms of channels, celebrities and increasingly professional content (Lange, 2014; Burgess and Green, 2018). In the years that followed, Morten Münster became one of the most famous Danish-speaking YouTubers, and often, his sister Naja appeared in the videos on his channel, which were watched by hundreds of thousands of people. In 2015, when she was six years old, Naja Münster’s own channel was launched; by 2019, it was attracting over 200,000 followers. Naja Münster ranks among the most followed Danish-speaking YouTubers, along with her brother Morten, their brother Max and their parents, Hanne and Finn, who are all producers of videos and other types of social media content.2 Her use of social media is embedded in shared activities in her family, for whom content production for social media is a hobby, a lifestyle and, increasingly, a source of income (Johansen, 2020).

Despite their many obvious differences, both Ida Thiele and Naja Münster represent to us privileged girls whose parents or other relatives provide them with high-quality media, allow them to develop the skills to use these media and thus allow them to speak, establish relationships and present themselves as first-person narrators in the popular media of their time.

Theory, Concepts and Methodologies

As we are interested in children as users, we apply the concept of ‘affordances’ to both cases discussed here. This term has been extensively used in media studies, particularly with reference to analyses of a variety of new media (Bucher and Helmond, 2017). More recently, the concept has also been applied to studies of children’s use of media in historical contexts (Christensen and Appel, 2021). Our analyses of children’s products, practices and voices do not rest on the idea that these sources represent or promise more truthful answers than other sources or methods. In that regard, we agree with Spyrou, who warns researchers against focusing on ‘the authenticity and truth of voice’ (Spyrou, 2018, p. 86) and argues that ‘a critical, reflexive approach to research in and with children’s voices needs to consider the actual research contexts in which children’s voices are produced and the power imbalances which shape them’ (p. 86).

As we wished to explore the media contexts and conditions that allowed Ida Thiele and Naja Münster to express themselves, we draw on Andreas Hepp and Uwe Hasebrink’s work (2018), which suggests that the empirical analysis of media practices extends its focus to communicative figurations. This concept includes an individual’s practices in ‘media environments’ (the media available at a given time in a given society), ‘media ensembles’ (media used in specific social domains, such as families) and ‘media repertoires’, which they define as ‘the individual’s selection of the media as they use and appropriate them as part of their everyday practices’ (p. 28). We draw on Marie-Laure Ryan’s broad definition of media as indicating both channels of communication and semiotic expression (Ryan, 2005), and apply Hepp and Hasebrink’s foundation in mediatisation theory, whereby we also understand contemporary media as structured through and by their commercial structures, especially the way in which today’s commercial media platforms are based on data collection as a defining logic (Hepp and Hasebrink, 2018, p. 16). As we discuss later in this article, this is an inescapable aspect of Naja Münster’s use of media platforms such as YouTube and TikTok.

The differing characteristics of our source material led us to apply partly differing methodologies to the two cases discussed here. In Ida’s case, her voice is present in the form, content and materiality of the letters, and an analysis of the letters is informed by the settings and the relationships of which they are a part. Furthermore, the letters present an interesting case, owing to their number and the long period over which they were written.

In Naja Münster’s case, it is possible to apply ethnographic methods, such as observation and interviews, to access her points of view and self-interpretation. In this case, the analysis is based on ongoing registration and classification of the videos uploaded to her YouTube channel since 2017 (approximately 300 videos to date), two qualitative, semi-structured interviews (one in the Münster family’s home in 2018 and one online via Skype in 2020), observations and interactions at two events where Stine Liv Johansen interviewed Naja Münster and her mother on stage in front of a child audience, and ongoing observations of related social media channels and other media, such as TV and newspapers, where the Münster family has appeared (see Johansen, 2021, for a full description and analysis).

The main argument for applying mixed methods to this study is that an exploratory, comparative approach to heterogeneous sources may draw attention to aspects of children’s experiences, actions and statements to which we would not have had access if the source material was more homogenous. With reference to Spyrou (2018), we acknowledge and appreciate the ‘messy’ nature of the data we have available for this study, and approach them as sources of knowledge that are relevant to specific children’s media practices. A further motivating factor for combining these approaches is the traditional segregation between literary studies and media studies, also in relation to texts produced and media used by children; finally, we wish to challenge the traditional reluctance of both these fields to regard children’s practices and productions as interesting and relevant objects of study.

When it comes to research ethics, each of the two cases presents grounds for specific consideration. Studying Naja Münster as an example of a child in contemporary media culture (Johansen, 2021) presents different challenges and opportunities than the study of Ida Thiele’s life in the 1830s. Because Naja Münster is a living person – and a child – appropriate measures are necessary to maintain a respectful relationship with her and her family, although anonymity cannot be provided (as we would usually do with study participants).

Ida’s letters were sources of information not only about herself, but also about her family. Letters would often be read aloud as entertainment for the whole family, and Ida’s father encouraged her to read his letters aloud, for instance, to her younger sister. Just M. Thiele saved Ida’s letters and she saved his and, at some point, they were either donated to or purchased by the Royal Danish Library.

Children as Users and Producers in Media Studies and Children’s Literature Studies

Although the ways in which children act as media users and producers of texts (e.g., on Instagram and YouTube) are widely discussed in public media, research on these topics is still scarce. Following the global spread of YouTube in particular (but also other social media networks and video-sharing platforms), which paved the way for new commercial structures and what has been referred to as micro-celebrity or influencer culture, scholars have turned their attention to the practices and constructions of these rather significant examples of digital celebrity culture (Senft, 2008; Jerslev, 2016).

Few studies of internet celebrity have focused specifically on young children as producers or co-producers of content. The term ‘kidfluencer’ – a child acting as an influencer on social media – is the subject of some scholarly work, but mostly from a reception and/or marketing perspective (e.g., Rasmussen, Riggs and Sauermilch, 2021), or from a critical perspective that focuses on the commercial and children’s rights aspects of young children appearing on social media platforms (Leaver, 2020). Although these aspects are important, Naja Münster’s case allows for a different approach that – some might argue – is less critical. Still, studying this case and relating it to Ida Thiele’s case identifies other equally relevant perspectives related to children’s roles as co-producers of media.

Until recently, children as media users and producers of texts have had a marginal presence in children’s literature studies. In Scandinavian countries, research on what may be called ‘children’s literary practices’ from a contemporary perspective has largely been lacking, with the noteworthy exception of some studies of children’s reading experiences (e.g., Mjør, 2009; Skaret, 2011; Hansen, 2014; Solstad, 2015). In contrast, scholars from English-speaking countries have identified the need to focus on children as producers and co-producers of texts, including in a historical perspective, rather than the passive – and irrelevant – receivers of literary texts (Gubar, 2014; Smith, 2017). However, these scholars include media other than printed books only to a very limited extent. A further difficulty is related to the fact that children’s writing is rarely published and kept in archives and collections (McGillis, 1991; Sánchez-Eppler, 2013; Appel and Christensen, 2017). A growing interest in children as (co-) producers of texts is reflected in an increasing number of publications focusing on contemporary children producing texts (Wesseling, 2019; van Lierop-Debrauwer and Steels, 2021), and there also seems to be an increasing interest in finding and analysing media content produced by children in collections and archives.

Jacqueline Reid-Walsh is one of the rare scholars who combines media studies’ and literary studies’ concepts to the study of children’s books. When she analyses nineteenth-century books and children’s agency, she argues that ‘the focal point in analyzing historical children’s media should be the child’ (Reid-Walsh, 2012, p. 165). In accordance with Gibson (1977), Reid-Walsh defines affordance as a ‘set of implied interactions for the interactor’ and ‘what is facilitated and what is restricted by the design and structure’, including ‘intentional and unintentional reading, viewing, and playing paths that may either accord or contradict the stated intent of the narrative’ (Reid-Walsh, p. 165–166). In a certain sense, there is a possible ‘crack’ (to use Mazzei’s term) between a medium’s ‘implied interactions’ and the extent to which children choose to accept or challenge the possible interactions afforded by a medium. As a concept, affordance encourages us to attend not only to what children say and what they are silent about, but also to what they choose to do or not to do with media. Thus, in the following section, we consider how specific media offer a child the opportunity to act in certain ways and how their use of these media make it possible to observe intentional and unintentional practices.

Ida Thiele’s and Naja Münster’s Choices of Content

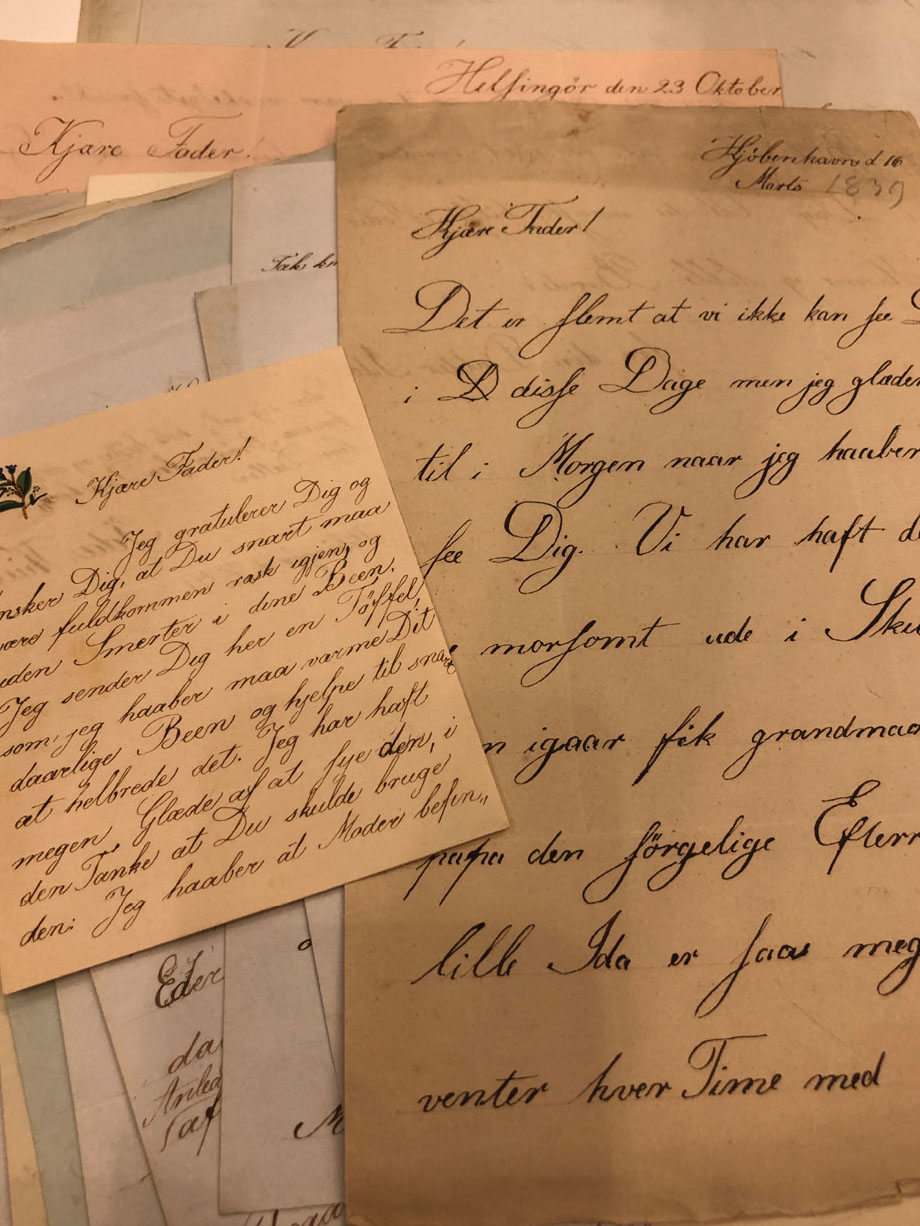

Ida Thiele was encouraged to produce and learn the conventions of letter writing because the letter was the principal means of private communication from the mid-eighteenth century onwards, including among children. In her letters, we can follow the girl’s emergent media literacy with regard to letter writing, as well as the ‘media repertoire’ of a young girl from around 1837, to use Hepp and Hasebrink’s term (2018). Furthermore, the letters give an impression of how various media enabled a young girl to express herself and interact with peers and relatives in the first half of the nineteenth century. Medium and content are intertwined in Ida’s letters: her early letters communicate that she is not only trying to learn how to use a pen, but also the conventions of the letter as a medium. Figure 1 presents one of the earliest preserved letters and, at a technical level, this letter reveals various challenges related to writing: mistakes and corrections indicate the difficulties of spelling, and the presence of ink spots demonstrates that writing with a pen is a complex skill. The presence of different styles of handwriting indicates the heavy demands on, and expectations of, a young girl from a cultivated and wealthy family.

At the same time, the tone of this letter is one of longing and a child’s wish to not only be able to write to her father, but to meet him in person. In the early letters, adults and children co-produce the letters: there are traces of pencilled lines, probably drawn by Ida’s teacher, and on one envelope, Ida Thiele seems to have written her father’s name in her own handwriting and an adult has added the same name in adult handwriting. In yet another letter, Ida Thiele writes that her teacher ‘was kind and drew them for me so I could paint them myself’ (undated letter, Ida Thiele, NKS 4437, III). Her agency and her ability to express herself depend on her relationships, in this case with her teacher and her father, who support the development of her media literacy and provide her with the necessary – and expensive – equipment.

Naja Münster is a co-producer of media content and uses various platforms to distribute various types of content. In this analysis, we focus on her use of YouTube. Her videos on YouTube reflect how her interests and her daily life have changed since she first appeared in videos on her brother’s channel. Many videos show Naja Münster as a child playing, acting out various narrative and playful tableaus. An early example (from 2016) shows Naja Münster as she decides to run away from home because her mother will not allow her to eat sweets on a weekday. This video has a clear script and Morten Münster is credited as the director. In a later example from 2018, Naja plays spa day with her Barbie dolls. This video is clearly less scripted, although the theme is fixed and the props (bowls with water, lotions, a toy cash register) are lined up; but the camera (held by her mother) registers the narrative that she plays out, and there is no visible interaction between Naja Münster and her mother. Special effects and music were added to the video during editing, emphasising specific parts of the storyline, but the video still follows what seems to be a mostly improvised play narrative.

Other videos show Naja Münster as what may be termed a playful child on YouTube. In these videos, she uses genres and styles from other YouTubers’ videos and remakes them according to her own, often childish, expression. One example appears in a video from 2016, where Naja Münster enacts a morning routine as a parody of a type of video often seen on older YouTubers’ and bloggers’ social media platforms. But when Naja Münster performs her morning routine, she eats a chocolate bar and goes straight back to bed, instead of inspiring her followers to drink healthy smoothies or take care of their skin as other influencers would do. In these videos, which are often as scripted as the first example described above, Naja Münster and her family may be said to engage in interpretive reproduction (Corsaro, 1993), which is characteristic of narrative and role play. In this case, however, they use media technologies with specific affordances (Bucher and Helmond, 2018) and share the staged play with a large audience.

A third type of content on Naja Münster’s YouTube channel has become increasingly apparent over the last couple of years. This is the type of content in which she no longer just pretends but rather internalises the styles and practices of social media influencers, and showcases her new clothing collection (2020) or vlogs from a film shoot in which she is involved. This type of content represents a degree of professionalisation and commercialisation that has become increasingly prominent on Naja Münster’s channel as she has grown older and her life has become structured by her activities as an influencer to a greater extent.

In both Ida’s and Naja’s cases, the content they produce reflects how they become familiar with the scripts and conventions surrounding the media they use, and also their interest in communicating: in Ida’s case, the emotions that convey her close relationship to her father, and in Naja’s case, the connection between her play and her productions. In the following section, the interplay between play and production becomes clearer, also in Ida’s case.

Girls’ Perspectives on the Purposes and Affordances of Media

According to Christian Gellert (1715–1769), a German author and expert on letter writing, the most important affordance of the letter as a medium is that it communicates a self-portrait of the author: a letter is ‘the proof whether our brain looks dark or light, orderly or disorderly, healthy or sick, if we know how to live or not; they are the means to provide us with esteem and love, to procure or prevent our happiness’ (Gellert, quoted in Christensen, 2009, p. 194–95).

From Ida’s point of view, what are the letter’s affordances? First, letters offer her the opportunity to communicate in the most fundamental sense. They are a way for her to stay in close contact with her father and preserve an intimate relationship across the distance that divides them. The presence of letters compensates for the absence of her father, for instance when she writes, ‘I long so much to know how you and mother [her father’s second wife] are doing because I have been here for a week now and not seen you, but in Copenhagen I saw you almost every day’ (undated letter in NKS 4437 III). The lack of commas and full stops may reflect Ida Thiele’s emerging writing abilities, but may also be interpreted as a sign of the impatience and eagerness of the child writer. Her statement points to the fact that the author knows that letters and language offer an accepted opportunity to express emotions.

For Ida, another affordance of the letter is that it gives her the opportunity to access new material that may increase and improve her production of media content for self-expression and entertainment; in this regard, her letters encourage a revision of contemporary ideas of children’s media repertoires and preferences in a historical perspective. Knowing that many books were produced for children at this time, books may be expected to be a central medium. But although she mentions some titles, other media and modes of expression play a larger part in her life, especially various dramatic texts. For instance, she asks her father to provide ‘paper to make small dolls for our theatre, for the dolls that come with it are so hideous (…)’ (Ida Thiele, undated letter NKS 4437, III). When her father sends her some adornments intended for her dolls, she replies: ‘No, we will adorn ourselves with them. And this is what we do when we perform comedies, which happens quite often (…)’ (Letter 6 November, no year NKS 4437, III). Ida Thiele’s intention of making her own dolls and her alternative use of the material sent to her may be interpreted as an example of the way children can be co-producers and actors who shape their own culture in relation to play.

Beside letter writing, Ida Thiele uses her body in various ways as an important means of communication. Various forms of dramatic performances, dance lessons and attendance at children’s balls are frequently mentioned in Ida’s letters. Histories of children’s literature in Denmark neglect drama completely, but reading a child’s statements in her letters sheds light on the important role of this genre, seen from a child’s point of view. In this case, attending to children’s voices when they discuss their media offers a corrective supplement to established histories of children’s culture.

YouTube is Naja Münster’s first choice of platform when it comes to presenting herself to her followers. YouTube allows for longer and more edited video formats than is the case with some of the other platforms she uses (e.g., Instagram). Hanne and Morten manage the editing, and Naja Münster is not very involved in this. YouTube does not allow the followers on Naja Münster’s channel to comment on her videos; this function is disabled (by the platform) on all children’s channels. For Naja, this means that she uses Instagram to interact with her followers through comments, chats and polls, and so forth. To set up a YouTube channel, the minimum age is 13; therefore Naja’s channel is formally owned by and administered by her mother. Although she has greater access to digital media than many children her age, Naja is still subject to restrictions, from both the platform’s general affordances and specific child-focused restrictions, and from her family through their regulation of and involvement in her communicative practices, to which we will return later.

YouTube is the medium Naja Münster has known throughout her childhood. This is the platform her family has used most, and the platform she herself uses for entertainment and inspiration. Increasingly, as she has grown older, other platforms have come to play a more prominent role, as she is able to manage and publish on these with greater autonomy – within constraints such as those described above.

Silencing Girls Across the Centuries: Conventions and Constraints

Ida Thiele generally accepts the conventions of the letter as a medium: she learns the fundamental formal principles, for instance, those concerning salutations, how to close a letter, and that the content may, and often does, include information about her health and that of her relatives, about daily life in the family, and about rare events such as parties or excursions. So, what is this girl silent about? The letters reveal that she has been taught not to complain or express emotions that would not be considered appropriate for a girl of the upper classes. For instance, accepted emotions are concern for the well-being of her father and other relatives, joy at participating in cultural or social events, or affection when sending home-made gifts to her father. She is generally silent when it comes to criticising the circumstances of her life. There are rare, subtle examples of criticism, for instance, when she writes about being taught grammar, that ‘it is not much fun, but it must be learned’ (Letter 6, December, no year). Apparently it is important, perhaps also to her grandparents, to communicate that she is happy. When she becomes a teenager, small signs of disappointment or disapproval of the adults’ decisions begin to appear, but only once, in a letter dated 6 August 1844, does she express a feeling of discontent: she had been talking to a guest who was telling her about his travels through Italy and she writes, ‘I only think it is hard [tungt] that only a few people may be so happy as to see something of the wonderful, big world, and that so many will never see more than the small place where they belong’. Subsequently, she writes that there must be reasons for this, and that one knows how to be very happy with what one has! The discrepancy between the two statements reveals a silence concerning the limited opportunities of even a privileged girl when it comes to leaving the protected life in the home and making such choices for herself.

Naja’s range of opportunities seems much broader at an immediate level, but structural limitations are quite powerful. One example illustrates this. Since its launch in 2016, TikTok has become one of the most popular and most used platforms among children, including Naja Münster and her school friends. Naja has tried to establish a profile on TikTok on several occasions, but each time her profile has been shut down by the platform, which does not (officially) allow children under the age of 13 to set up a profile. However, many younger children do have profiles on TikTok, but if they do not have a large number of followers, in many cases, they are able to go ‘under the radar’ on the platform. This is not the case for Naja, as she quickly attracts a substantial number of followers every time she announces that she has a new TikTok channel. The platform administrators recognise this and ban her from the platform. She now awaits her 13th birthday, when she will be able to legitimately set up a profile on TikTok like so many other children her age.

Discussion and Conclusion

Among the general public, discussions of children’s media use often focus on changes and what are regarded as new aspects of children’s media use. Close readings of Ida Thiele and Naja Münster as media users and producers of text over time shed light on some of the continuities and changes, differences and similarities among children as users and producers of media texts, and the conceptual and methodological approaches to such cases.

At a methodological level, in both cases discussed here it seems fruitful to pay attention to the media repertoires children create from the media ensembles available in their social settings. This conceptual framework allows us to see how children combine and use media in creative ways that are relevant to their circumstances and aspiration to communicate with others. The term ‘affordance’ also seems applicable and relevant to the study of historical and contemporary cases, as suggested by Reid-Walsh (2012). A focus on the affordances of specific media draws the researcher’s attention to children’s possible use of specific media, and our analyses of the two girls’ media products testify to their actual use.

Both analyses indicate certain structural and contextual limitations related to Ida Thiele’s and Naja Münster’s use of media. One of the most important differences between the ways in which the two girls use media in networks of peers, parents, platforms and commercial media structures relates to the final item in this list (commercial media structures). Ida Thiele grew up in a very wealthy family and had access to media tools, toys and a family structure that allowed and encouraged her to spend time on leisure activities such as letter writing. This was a result of her social and cultural circumstances, her upbringing and her personal interests. On the other hand, Naja Münster is a child of the Danish welfare state, and she has broad access to digital media, owing to general media developments and the widespread digitisation of Danish society. But the commercial aspects of her media use include the fact that she – and her parents – earn money from the videos she produces and (increasingly) from the commercial partnerships and deals in which she is involved. Her audience may not be as large as the audiences of international social media influencers, but it is significant.

Another important difference between the media practices of the two girls relates to the structures and norms to which Naja Münster’s media use is subject. Both girls act according to certain norms and ideas about what a girl their age may or should do in the specific historical and cultural contexts in which they live. But for Naja Münster, part of this context includes the extensive commercial media structures, which include content moderation, monetisation and changing affordances of the platforms she uses and the business of which she has become a part (Johansen, 2020).

Returning to Spyrou’s (2018) warning not to seek authenticity or essential truths in children’s voices, we do not claim to have found such truths. Spyrou notes the importance of paying attention to the contexts from which children’s voices emerge, and states that we if we do this and include reflections on the discursive contexts that inform children’s voices, ‘we can move beyond simplistic claims to truth and authenticity and begin to look critically at issues of representation’ (Spyrou, 2018, p. 86). However, Spyrou also states that one way to move beyond essentialism when trying to listen to children is to ‘make transparent the very processes which produce children’s voices’ (p. 109).

We argue that children’s media practices are fundamental aspects of the presentation of children’s voices, and that the way children choose to present themselves through media is an important part of a complex picture. In both respects, attending to children’s voices through the media they use provides researchers with new insights. We do not wish to downplay the many differences between the two girls discussed here, or the historical and cultural differences surrounding them. However, the insights we have gained from our comparative analysis encourage us to explore the theoretical and analytical frameworks of other examples throughout history, with a view to learning more about children’s choices and opinions with regard to the media available to them, and those they choose to use.

References

- Appel, C. and Christensen, N. (2017) Follow the child, follow the books. Cross-disciplinary approaches to a child-centred history of Danish children’s literature 1790–1850, International Research in Children’s Literature, 10(2), pp. 194–212.

- Bucher, T. and Helmond, A. (2017) The affordances of social media platforms, in Burgess, J., Marwick, A. and Poell, T. (eds.) The SAGE handbook of social media. London: Sage Publications, pp. 233–253.

- Burgess, J. and Green, J. (2018) YouTube: Online video and participatory culture. 2nd edn. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Christensen, N. (2009) Lust for reading and thirst for knowledge: Fictive letters in a Danish children’s magazine of 1770, The Lion and the Unicorn, 33(2), pp. 189–201.

- Christensen, N. and Appel, C. (2021) Children’s literature in the Nordic world. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- Corsaro, W. A. (1993) Interpretive reproduction in children’s role play, Childhood, 1(2), pp. 64–74.

- Gibson, J. (1977) The theory of affordances, in Shaw, R. and Bransford, J. (eds.), Perceiving, acting, and knowing: Toward an ecological psychology. Hillsdale: Lawrence Earlbaum, pp. 67–82.

- Gubar, M. (2014) Entertaining children of all ages: Nineteenth-century popular theater as children’s theater, American Quarterly, 66(1), pp. 1–34.

- Hansen, S. R. (2014) Når børn vælger litteratur. Læsevaneundersøgelse perspektiveret med kognitive analyser. Dissertation, Aarhus University.

- Hepp, A. and Hasebrink, U. (2018) Researching transforming communications in times of deep mediatization: A figurational approach, in Hepp, A., Breither, A. and Hasebrink U. (eds.), Communicative Figurations. Transforming Communications. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 15–48.

- Humphreys, L. (2018). The qualified self. Social media and the accounting of everyday life. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- James, A. and James, J. (2011) Key concepts in childhood studies. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- James, A. (2007) Giving voice to children’s voices: Practices and problems, pitfalls and potentials, American Anthropologist, 109(2), pp. 261–272.

- Jerslev, A. (2016) In the time of the microcelebrity: Celebrification and the YouTuber Zoella, International Journal of Communication, 10, pp. 5233–5251.

- Johansen, S. L. (2021) Münster’s Inc. Children as influencers balancing celebrity, play and paychecks, in de la Ville, V., Garnier, P. and Brougère (eds.) Cultural and Creative Industries of Childhood and Youth. Bruxelles, Belgium: Peter Lang Verlag.

- Lange, P. G. (2014) Kids on YouTube: Technical identities and digital literacies. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press.

- Leaver, T. (2020) Balancing privacy. Sharenting, intimate surveillance, and the right to be forgotten, in Green, L., Holloway, D., Stevenson, K., Leaver, T. and Haddon, L. (eds.) The Routledge companion to digital media and children. London: Routledge.

- Lierop-Debrauwer, H. van and Steels, S. (2021) The mingling of teenage and adult breaths. The Dutch Slash series as intergenerational communication, in Deszcz-Tryhubczak, J. and Jaques, Z. (eds.) Intergenerational solidarity in children’s literature and film. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, pp. 218–230.

- Mazzei, L. A. (2009) An impossibly full voice, in Jackson, A. and Mazzei, L. (eds.) Voice in qualitative inquiry: Challenging conventional, interpretive, and critical conceptions in qualitative research. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 45–62.

- McGillis, R. (1991) Famous last words, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 16(4), pp. 230–231.

- Mjør, I. (2009) Høgtlesar, barn, bildebok: Vegar til meining og tekst. Dissertation, University of Agder.

- Rasmussen, E., Riggs, R. and Sauermilch, W. S. (2021) Kidfluencer exposure, materialism, and U.S. tweens’ purchase of sponsored products, Journal of Children and Media, 16(1), pp. 68–77.

- Reid-Walsh, J. (2012) Activity and agency in historical ‘playable media’, Journal of Children and Media, 6(2), pp. 164–81.

- Ryan, M.-L. (2005) Media and narrative, in The Routledge companion of narrative theory. London: Routledge, pp. 288–292.

- Sánchez-Eppler, K. (2013) In the archives of childhood, in Duane, A. M. (ed.) The children’s table. Childhood studies and the humanities. Athens: University of Georgia Press, pp. 213–237.

- Senft, T. M. (2008) Camgirls: Celebrity and community in the age of social networks. New York: Peter Lang.

- Skaret, A. (2011) Litterære kulturmøter. En studie af bildebøker og barns resepsjon. Dissertation, University of Oslo.

- Smith, V. F. (2017) Between generations. Collaborative authorship in the golden age of children’s literature. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

- Solstad, T. (2015) Snakk om bildebøker! En studie av barnehagebarns resepsjon. Dissertation, University of Agder.

- Sparrman, A. (2019) Configuring the doers, in Sparrman, A. (ed.) Making culture. Children’s and young people’s leisure cultures. Gothenburg: Kulturanalys Norden, pp. 150–154.

- Spyrou, S. (2018) Disclosing childhoods. Research and knowledge production for critical childhood studies. London: Palgrave.

- Spyrou, S., Rosen, R., and Cook, D. T. (2018) Introduction: Reimagining childhood studies: Connectivities … relationalities … linkages …, in Spyrou, S., Rosen, R. and Cook, D. (eds.) Reimagining childhood studies. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 1–20.

- Wesseling, E. (2019) Researching child authors: Which questions (not to) ask. Humanities, 8(2). n. pag. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8020087

Oral sources

- Interviews (2017; 2020) by Johansen, S. L. with Naja Münster and Hanne Münster, and with manager Cecilie Blaksted, Splay One.

Letters in archives

- Letters from Ida Wilde, born Thiele, manuscript collection of the Royal Danish Library, NKS 4437, 4°, III.

Notes

- 1. The manuscript collection at the Royal Danish Library in Copenhagen contains 203 letters written by Ida Thiele to her father between c.1837 and 1859. About 50 of these letters were written when she was between 7 and 15 years old. This same collection contains 42 letters from Just Mathias Thiele to Ida, dated from 1 June 1836 onwards.

- 2. In 2018 and 2019, the highest earning YouTuber in the world was the then eight-year-old Ryan Kaji of Texas, who has over 24 million followers. The commercial aspects of Naja Münster’s social media presence are by no means comparable to those of Ryan’s World